Destination Choice: Theoretical Foundations

This page is part of the Category [.

Three primary theoretical starting points for developing destination choice models dominate current practice:

- Gravity models.

- Entropy maximization (also known as information minimization) models.

- Random utility models.

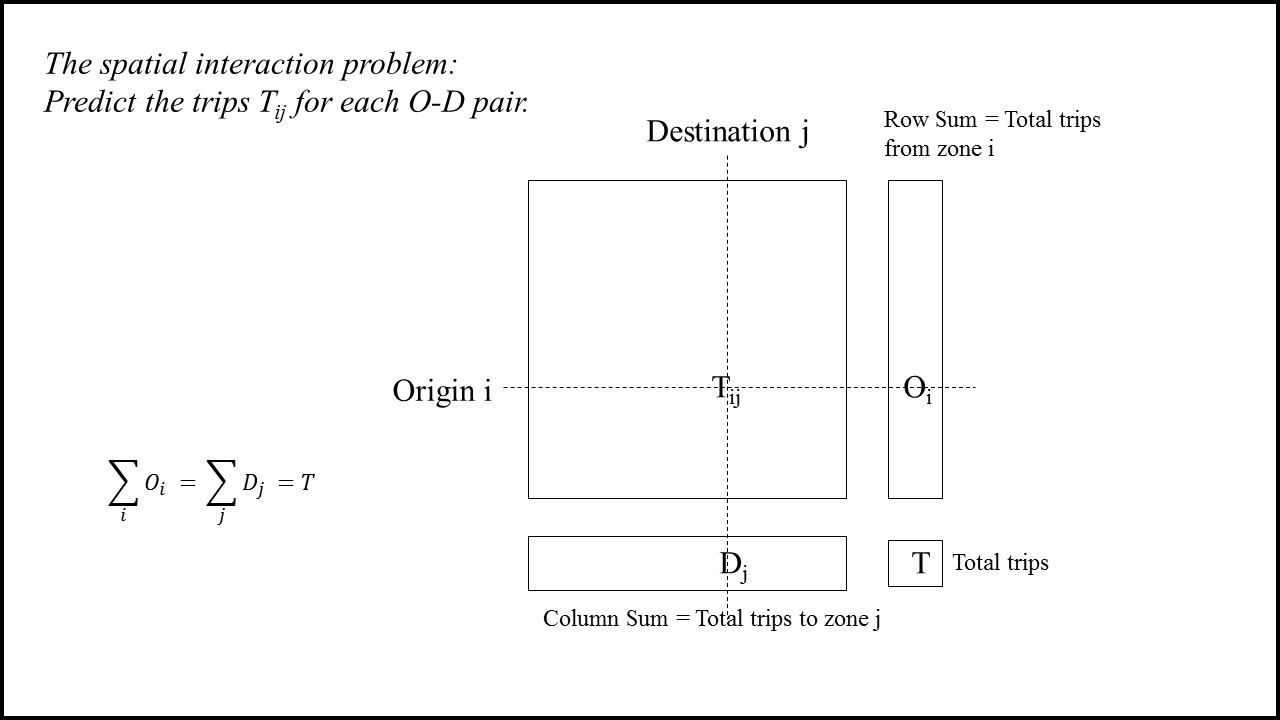

These three modeling approaches are, under appropriate assumptions, mathematically equivalent, and so are special cases of what can be generally called spatial interaction models. All these models attempt to address the same problem, as illustrated in Figure 1, in which spatial interactions (usually trips) between locations in space (typically traffic zones) are to be predicted, given limited, more macro, information concerning these interactions, such as the number of trips originating in each zone and/or the number of trips destined to each zone.

# Gravity Models

Gravity models have been in use by geographers, market researchers, transportation modelers and many others for well over a hundred years. The starting point for these models, as the name implies, is Newton’s Law of Gravity:

(1)

where

Gravity models of human spatial interaction adopt the same assumption: the amount of interaction between two locations (usually represented by trips, but could also be flows of money, information, etc.) is proportional to the “size” (“attractiveness”) of the two locations and the extent of their physical separation (measured in distance or travel time). That is, gravity models assume:

or,

where

(2)

The constant k is chosen so that (2) satisfies known constraints on the interactions being predicted. If, for example,

(3)

(4)

Equation (4) is called a singly-constrained gravity model, since only a single constraint (equation (3)) has been imposed on the model. Very many examples of singly-constrained destination choice models exist, in a variety of applications. In particular, note that instead of constraining the predicted trips to match predetermined trip origin totals (an origin-constrained model), it would have been possible to constrain the trips to sum to predetermined trip destination totals instead (a destination constrained model).

In some cases, such as predicting work locations, it may make sense to constrain the predicted origin-destination (O-D) trips to equal both trip origin and trip destination totals (as typically determined by trip generation models). In this case,

(5)

Imposing both constraints (3) and (5) on the model results in a doubly-constrained gravity model, which can be expressed as:

(6)

where

# Entropy Maximization Models

While it is intuitively plausible that should trips go to “bigger” (more attractive) destinations as well as to destinations that are closer to, rather than farther from, the trip origin, gravity models have always been criticized for their apparently ad hoc derivation: why should human interactions necessarily follow the same “law” as gravitational bodies? Beginning with Alan Wilson’s seminal paper in 1967,[1] a sound statistical theory underlying gravity models was developed. Wilson showed that the statistically most likely trip matrix, T, is given by maximizing the entropy function:

(7)

subject to known constraints. In the case of a doubly-constrained model, at a minimum, these are constraints (3) and (5), plus typically a third constraint which often takes the form:

(8)

where T is the (known) total number of trips in the system, and

Solving this mathematical program yields the following trip distribution model:

(9)

where

(10.1)

(10.2)

It can be shown that

(11)

This is exactly the doubly-constrained gravity model (equation (6)) with the specific impedance function

A specific entropy model specification is determined by the choice of constraints imposed on the model. The general procedure for specifying an entropy model is defined below. Arbitrarily complex specifications can be generated, providing that an appropriate constraint set can be specified.

In particular, the impedance functional form derives from the constraint(s) written concerning transportation level-of-service variables. In the example above, imposing the constraint that the predicted system-wide average travel should equal the observed average time in the base data yields a negative exponential impedance function. If instead, one wrote a constraint in which the predicted average of

# Random Utility Models

By far the most common type of destination choice model used in practice is some form of random utility model, usually a multinomial logit model or a nested logit model (e.g., a nested destination-mode choice model). Random utility (discrete choice) models are used throughout travel demand modeling given their strong theoretical foundations in microeconomic theory and their practical and efficient analytical function forms.

A typical logit destination choice model for the probability that destination j is chosen given trip origin i

(12)

where

- Flexibility in specifying the utility function (any relevant variable can be readily included).

- Readily available parameter estimation software.

- Familiarity with the method.

- Computational efficiency.

- Support for both disaggregate (person-level) and aggregate (trip flows) formulations.

Detailed discussion of the specification and use of logit destination choice models is provided on many other pages throughout this wiki.

Mathematical Equivalence of Gravity, Entropy and Logit Models

It is commonplace in the literature to state that “destination choice” (i.e., disaggregate logit) models are superior in performance to “gravity models”. This, however, is a somewhat misleading statement in that it reflects the common practice in terms of how “gravity” and “logit” models are typically implemented, rather than fundamental differences in the mathematics of the two approaches. In practice, “gravity” models are often aggregate (based on O-D flows instead of individual trips) and very simply specified in terms of both attraction/size variables and impendence functions (including sometimes the use of distance rather than travel times). “Logit” models, on the other hand, are usually disaggregate (based on individual trips) and can have an extensive set of explanatory attraction variables in the utility function. Given this typically more extensive set of explanatory variables, it is not surprising that such “logit” models outperform the more simply specified “gravity” models.

But, as Daly (1982),[2] first observed, gravity models can be shown to be a special case of nested logit models where the nests are degenerate, aggregate alternatives. Simiilarly, Anas (1983)[3] observed, “gravity” models as derived through entropy maximization can be formulated at the disaggregate (individual trip) level as well, and can incorporate any number of explanatory variables. In particular, any linear-in-the-parameters utility function typically used in logit destination choice models can be replicated in an entropy model. Further, if consistently defined at the same level of aggregation, the same set of explanatory variables and the same base data are used for parameter estimation, then it can be shown that the estimated parameters for the two models will be identical. Thus, logit and entropy (gravity) models are, in fact, not different models but are mathematically the same model.

As a simple illustration of this, equation (4) can be rearranged to yield:

where:

(13)

If we assume that:

(14)

Equation (14) is a simple logit destination choice model.

This mathematical equivalency with entropy models only holds for multinomial logit models, not for random utility models in general. The ability to theoretically derive logit models from two very different starting points, one behavioral (people choose alternatives so as to maximize their personal utility) and one statistical (deriving most likely choice probabilities given known constraints on these probabilities), however, is striking and arguably reinforces the case for use of logit models in applications where the underlying assumptions of the model (e.g., statistical independence of the alternatives) holds.

# Other Destination Choice Model Formulations

Historically, other approaches to destination choice models have been developed, including intervening opportunities models and competing opportunities models. In general, these approaches tend to be computationally more intensive without generating improved fits to observed data than more conventional methods and so are rarely used in current practice. Brief descriptions of these methods are provided here for historical documentation.

# Intervening Opportunities Models

The intervening opportunities model was first proposed by Stouffer (1940)[4] and extended by Schneider (1960)[5] and Golding and Davidson (1970)[6]. Stouffer’s original model hypothesized that the number of O-D trips from zone

(15)

where k is a constant of proportionality that ensures that all trips from zone i are distributed to destination zones.

Schneider expressed the model in terms of a differential equation:

(16)

Where:

Integrating equation (16) yields:

(17)

where

Hutchinson (1974)[7] presents a detailed discussion of intervening opportunities models.

# Competing Opportunities Models

Competing destinations models (Fotheringham, 1983) have received a fair amount of attention in the geography literature. They have been used in practice by at least one transportation planning agency. Fotheringham’s technique, which introduces an accessibility measure, has now become a common best practice in destination choice modeling (following Bhat et al., 1998).

# Doubly-Constrained Gravity/Entropy Models

# Gravity Formulation

Given observed or predicted trip origins, Oi and destinations,

(18)

(19)

(20)

Equation (20), however, will not satisfy constraint (19) except, perhaps, in the most trivial cases. The only way that a spatial interaction model can satisfy both the “row constraints” (18) and the “column constraints” (19) is through an iterative solution procedure in which the actual “attraction term”

(21.1)

(21.2)

(22)

Where

(23)

# Entropy Formulation

The equivalent entropy formulation involves solving the following mathematical program:

(24)

(25)

Using the method of Lagrange to maximize (24) subject to the equality constraints (18), (19) and (25) eventually yields the solution:

(26)

where β is an estimated parameter (

To numerically compute the balancing factors, the Bj terms can be initialized to 1.0, the Ai terms can be computed given these Bj’s, and the algorithm iterates until the factors converge to stable values.

A common criticism of doubly-constrained gravity models is the supposedly ad hoc nature of the balancing procedure using the “modified attraction terms” described above. As shown by the entropy model formulation, however, a doubly-constrained matrix can only be computed iteratively: no analytical closed-form solution is possible. Further, with manipulation, it can be shown that

# Estimating Gravity/Entropy Model Parameters

Various ad hoc procedures are sometimes used to estimate gravity model parameters. Given the entropy interpretation of the gravity model, however, the method for parameter estimation is unambiguous: parameters must be chosen so that the underlying constraints of the model hold. For example, for the simple doubly-constrained model given by equation (26) the parameter

Further, in the case of singly-constrained models gravity/entropy models the set of constraints generating the set of parameters to be estimated are exactly the set of equations defining the first-order conditions for maximizing the long-likelihood function for the corresponding multinomial logit model. Thus, standard logit model parameter estimation procedures can be used.

# Developing an Entropy Model

Explanatory variables are entered into an entropy model by writing a constraint for each variable. In the sections above, travel time was entered into the model by writing a constraint involving it (predicted average time = observed average time). This can be repeated for as many variables as desired. As an example, consider a singly- (origin-) constrained shopping destination choice model in which one wants the following explanatory variables to enter the impedance (utility) function:

ln(Fj) (where Fj is the amount of retail floorspace in zone j) A “dummy variable” CBDj (where CBDj = 1 if zone j is in the city’s central business district).

The full mathematical program to solve to generate this model is:

(28)

(29)

(30)

(31)

(32)

To maximize, solve the first-order optimality conditions:

(33)

Substituting (33) into (29) and solving for

(34)

Substituting (34) into (33) yields:

(35)

Equation (35) is the desired singly-constrained entropy trip destination model. Note that it can be rewritten as:

(36)

which is often the format used for “gravity” models.

Equation (35) also defines the destination probability choice model:

(37)

As previously discussed, equation (36) is a multinomial logit model, which can be estimated using standard logit estimation software.

# References

Content Charrette: Destination Choice Models

Wilson, A.G., “A Statistical Theory of Spatial Distribution Models”, Chapter 3 in R. Quandt (ed) The Demand for Travel: Theory and Measurement, Lexington, Mass: Lexington Books, 1970, . 55-82. ↩︎

Daly, A. (1982) 'Estimating Coice Models Containing Attraction Variables', "Transportation Research, Part B: Methodological" Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 5-15 ↩︎

Anas, A., “Discrete choice theory, information theory, and the multinomial logit and gravity models”, Transportation Research B 17, 1983, 13-23. ↩︎

Stouffer, S.A. (1940) “Intervening Opportunities: A Theory Relating Mobility and Distance”, American Sociological Review, 5(6), 845-867 ↩︎

Schneider, M. (1960) Panel Discussion on Inter-Area Travel Formulas, Bulletin No. 253, Highway Research Board, Washington, D.C. ↩︎

Golding, S. and K.B. Davidson (1970) A Residential Land Use Prediction Model for Transportation Planning, Proceedings, Australian Road Research Board,, Melbourne, 5-25 ↩︎

Hutchinson, B.G. (1974) Principles of Urban Transport Systems Planning, New York: McGraw-Hill ↩︎