Autonomous vehicles: use cases

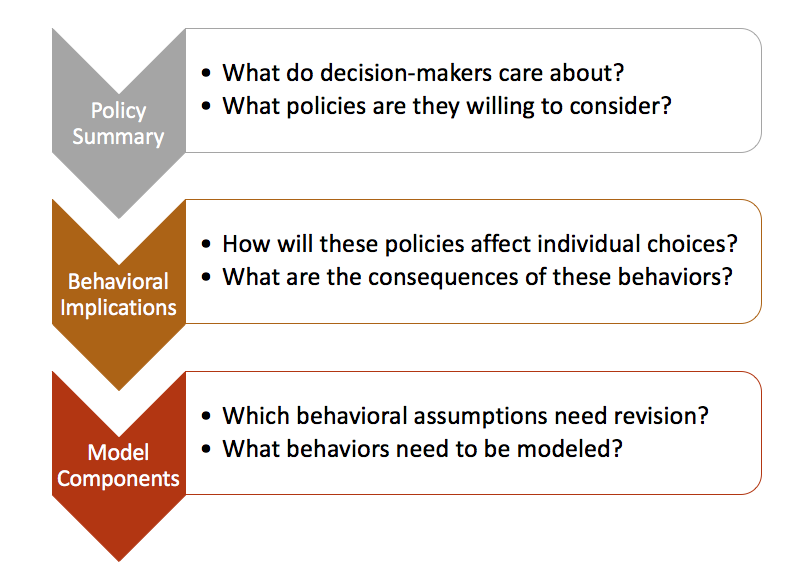

Models are designed to inform policy decisions, not to predict the future. Thus, it is difficult to specify a particular model form that is useful or needed for every possible CAV scenario. Instead, you should consider the policies that decision makers want to address, what behaviors may result from those policies, and then finally consider what model forms or components will address those behaviors. This process can be considered a recipe, illustrated below.

As an example, if policy makers are considering incentives for shared CAV ownership as opposed to private ownership, it may be prudent to carefully model the behavioral decisions involved in this tradeoff; otherwise, efforts might be better spent elsewhere. On this page, we walk through this process for three separate policies:

1. Road widening projects will cease, and funds will be diverted to other uses

2. Some freeway lanes will be dedicated for CAV use

3. Authorities will levy an occupancy-differentiated VMT tax

# Use Case: No More new Roadway Capacity

CAVs have the potential to dramatically improve the effective roadway capacity of existing infrastructure[1]. Policy makers are therefore being asked to make very difficult decisions in the context of long-range planning. Specifically: should their jurisdictions continue to invest in additional roadway capacity? Widening roadways is generally very expensive and requires long lead times and allocating resources to widening roadways means not allocating resources to other purposes, such as operational or maintenance purposes. When combined with the political costs of constituents dealing with congestion, policy makers could benefit from as much information as possible to guide them in making these decisions. It is very complicated to think through the competing impacts of population growth and technological change.

# Policy Summary

- Goal: efficiently allocate scarce resources.

- Policy: reallocate resources from constructing additional physical roadway capacity (i.e., no new lane-miles) in congested corridors to operational/non-physical-capacity-increasing projects.

# Behavioral Considerations

Travel models typically assume that congestion in no-build scenarios will increase proportionately with the population if no new capacity is added. In this policy scenario, the increased capacity comes from CAV technology rather than new lane-miles. It is an open question as to whether the technology improvements will outpace population growth, and the behavioral responses to this policy could therefore trend down two paths. If technology adds new capacity faster than population grows, then recurring congestion and peak period travel times will decrease. Coupled with lower values of in-vehicle travel time, the following behaviors are likely to emerge immediately:

- Longer automobile trips

- Mode shift towards automobiles and away from transit or non-motorized modes

Over time, longer-term behaviors may emerge:

- People will choose residential and workplace locations that are located further apart

- People will purchase CAVs to maximize their mobility and comfort while traveling long distances.

These changing behaviors could mitigate some of the benefits seen from technological improvements. Conversely, if population grows faster than CAV technology the behavioral changes are likely to be inverted. For example, the benefit of owning a personal CAV is lower for the short trips that are more likely in congested areas, and therefore shared ownership or hired rides from TNCs may be more common.

This policy is not explicitly concerned with behaviors such as household tour coordination or drop-and-hide (off-site) parking, though the feasibility of various daily patterns might change depending on vehicle availability.

# Modeling Framework

To represent the immediate behavioral responses to this policy in a travel model, you will need to do at least three things:

- Modify the highway volume-to-capacity functions to reflect higher capacities at higher volumes.

- Lower the in-vehicle value of time coefficient for automobile trips

- Feed back congested travel time skims into the destination choice and mode choice models.

The degree to which these coefficients or functions may shift is unknown, and speaks to the need for scenario testing and risk analysis. Understanding the effects of secondary behaviors may require:

- Automobile ownership models that distinguish between AVs and conventional vehicles

- Residential and firm location choice models

- Land use models

# Use Case: Dedicated CAV Lanes

The deployment of CAVs can potentially be accelerated with dedicated infrastructure (TODO: ADD REFERENCE). It is simply easier to operate a vehicle in a controlled environment free of conflicts. As such, policymakers may be interested in the potential costs and benefits of allocating a freeway lane, in this example, to automated vehicles. Travel models can likely provide useful insights to the potential impacts of these decisions under a range of automated vehicle adoption/penetration rates.

# Policy Summary

- Goal: efficiently utilize existing infrastructure

- Policy: dedicate an existing general purpose travel lane on a freeway for the exclusive use of CAVs

# Behavioral Considerations

The immediate response of this policy is to decrease the travel time on long-distance CAV trips. Short-distance trips likely will not benefit from improvements to limited access facilities. This will lead to a number of primary effects:

- Households will purchase an CAV to use the new infrastructure

- People may share an CAV rather than take mass transit

- Increased trip lengths for discretionary trips

- People making trips that are not now being made will be made (latent demand)

Secondary effects may include

- Adjusted workplace and residence locations

It is worth noting also that the travel time benefits of this policy are likely to diminish as CAVs earn a progressively larger market share. Therefore, this is likely to be a short-term policy and may not benefit from long-range horizon planning.

# Modeling Framework

The following model adjustments will be necessary immediately:

- Add CAV-only links to the model network

- Include CAV as an alternative in the mode choice model

- Calculate CAV travel times and feed back into destination choice and mode choice

Because this policy is specifically targeted to accelerate CAV adoption, a vehicle ownership model that includes CAV as an alternative and that is sensitive to CAV accessibility is desirable.

# Use Case: Occupancy-differentiated Vehicle-miles Traveled Tax

A potential drawback to the wide-scale deployment of CAVs is that they may harm the environment and/or the public realm by avoiding storage fees and/or optimizing the experience of their owner/customer by engaging in passenger-free travel. For example, an automated vehicle may circle the block to avoid paying a parking/storage fee while their owner/customer shops for groceries. Or, an CAV may drop its passenger off at work and then move to a remote location far away to be stored for the day, returning later to retrieve the passenger.

In addition to the concerns about zero passenger travel, urban planners have long been frustrated with the inefficiency of single-occupant vehicle travel and have long advocated for schemes such as high-occupancy vehicle lanes that make more efficient use of existing infrastructure.

An occupancy-differentiated vehicle-miles traveled tax has the potential to mitigate the impacts of both of the above behaviors (as well as raise revenue), by increasing the relative price of automobile travel with one or fewer passengers. Travel models can likely usefully contribute to this conversation across a wide range of automated vehicle adoption/penetration rates.

# Policy Summary

- Goal: efficiently utilize existing infrastructure

- Policy: charge vehicles a usage tax based on distance traveled and number of occupants, with a steep fee charged to zero-occupant vehicle movements.

# Behavioral Considerations

The immediate behavioral responses to this policy would be for households to consider shortening their trips and/or increase their vehicle occupancy. This will lead to a series of primary behavioral changes:

- Greater intra-household tour coordination

- More shared rides with people outside households

- Less last-mile access to mass transit stations

- Fewer dead-head trips, with reduced off-site parking

- Discretionary activities would move closer

The secondary impacts are important as well:

- Increased substitution of travel with teleworking and online shopping

- Fewer people will own personal CAVs, and will instead hire rides from TNCs

- TNCs will have higher fares, but will optimize their services to minimize their tax burden

- Altered land use patterns

The advantage of short trips will marginally change residential and firm location decisions, changing land use patterns. Alternatively, people may substitute travel with teleworking and online retail. The tax may dissuade some households from purchasing an CAV at all. TNCs operating fleets of for-hire CAV’s will therefore have a larger potential passenger base, though they will pass through the tax to their customers in higher fares; they will also face strong incentives to minimize their tax burden through network optimization.

Another consideration is people are relatively insensitive to hidden costs. If the tax is assessed in the form of a periodic bill instead of an up-front fare, then the behavioral effects of this tax on individuals will be minimal. TNC’s, however, would still face strong incentives to optimize.

# Modeling Framework

Modeling the behavioral changes of this policy will require elements not frequently found in extant travel models. To model the primary behavioral impacts, the mode will need:

- Mode choice including hiring or sharing CAVs, either for main the trip or for transit access.

- Separate travel time and travel cost values that vary by occupancy

- Coordinated household activity patterns considering mode and destination accessibilities

The secondary behaviors will need a different set of modeling tools:

- Vehicle allocation model to consider empty trips and inform household coordination

- Vehicle ownership model considering differential CAV accessibilities

- Residential and firm location choice

- Land use model

# Epilogue

In each use case, the resulting model framework is shaped by the policies it wishes to inform and not by an archetypical collection of necessary model components. This ensures that the model is relevant to the decisions it will study and not simply an exercise in behavioral complexity.

# References

Content Charrette: Autonomous Vehicles

Highway Capacity Benefits from Using Vehicle-to-Vehicle Communication and Sensors for Collision Avoidance, by Patcharinee Tientrakool, Ya-Chi Ho, and Nicholas F. Maxemchuk. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6093130/ (opens new window) ↩︎