Travel Demand and Network Model Integration Schemas

# Practical Integration Schemas

Four principal practical integration schemas exist as the consequence of two principal demand model structures (Trip-based and Activity-based models) and two principal network model structures (Static Assignment and Dynamic Assignment) that can be combined in any possible way.

| Static User Equilibrium Assignment | Dynamic Traffic Assignment (DTA) | |

|---|---|---|

| Trip-Based | (1) Conventional, well-established | (3) Usual for DTA in practice |

| Activity-Based | (2) Usual for ABM in practice | (4) Most advanced integration (first attempts) |

# (1) Trip-based / Static User Equilibrium Assignment

Theory and practice of integrated demand-network models have a long history dated back to the fundamental works of Evans (1976), Florian (1977) and others. The basic idea of these integrated formulations was that that the demand part of the model can be expressed as a set of entropy-maximization terms (Wilson, 1970) while the network part of the model can be expressed as a set of link-based congestion terms (Beckman, 1956).

# (2) Trip-based / Dynamic Traffic Assignment

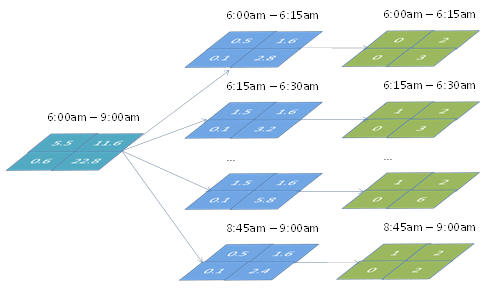

Up to date, most applications of Dynamic Traffic Assignment (DTA) were based on fixed demand inputs from 4-step models. This partial (one-way) integration often requires steps to convert the trip-based model output to a compatible temporal and spatial resolution of the DTA. Commonly, trip-based models operate with few time-of-day periods (such as AM Peak, Midday, PM Peak, Night). Some models generate daily travel demand only. DTA requires finer demand slices (such as 15 min). Trip-based models generate travel demand in floating (real) numbers, while DTA require discrete trips (in integer numbers). Split factors are normally applied (developed from household travel surveys or traffic counts) with subsequent rounding as shown the Figure below:

# (3) Activity-based / Static User Equilibrium Assignment

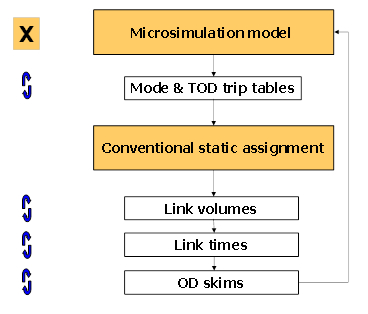

Activity-based (ABM) can generate complicated trip chains as discrete trips for individual agents. Most ABM applications are coupled with static user equilibrium assignments. There are two good reason to integrate with an UE assignment: For one, the UE assignment is an established method that is easier to implement than a DTA, and secondly, the UE assignment tends to run faster than DTA models. Averaging can be applied simultaneously to several components of the model as shown in the figure below (Vovsha, et al, 2008).

# (4) Activity-based / Dynamic Traffic Assignment

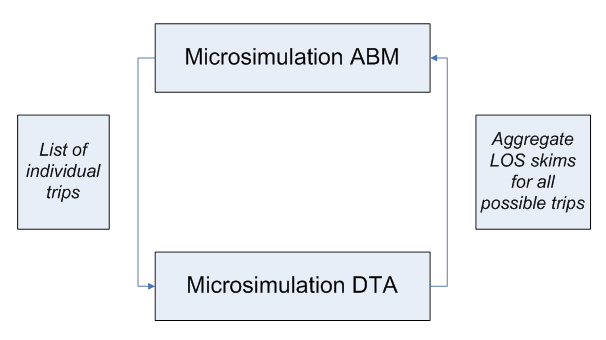

The integration of Activity-based models (ABM) with Dynamic Traffic Assignment (DTA) has been accomplished successfully, but remains the exception. Recent research projects including SHRP 2 C10 and L04 as well as the Chicago ABM-DTA integration project explored several new ways for such an integration that include a principally new notion of temporal equilibrium and individual schedule consistency that cannot be achieved with aggregate models. As shown in the figure below, one of the possible solutions is to employ DTA to produce aggregate Level of Service (LOS) matrices (the way they are produced by STA), and use these LOS variables to feed the demand model. This approach, however, would lose most of the details associated with DTA and the advantages of individual microsimulation (such as the individual variation in Values of Time or other person characteristics). In this approach, the individual schedule consistency concept is of limited value because travel times will be very crude for each particular individual. Nevertheless, this approach has been adopted in many studies due to its inherent simplicity (Bekhor et al. 2011, Castiglione 2012). The emphasis in these studies was to use more disaggregation in the LOS skims – many more time periods, smaller zones and several VOT classes. But at some point, this may also become unmanageable because of the sheer amount of data.

# New Methods

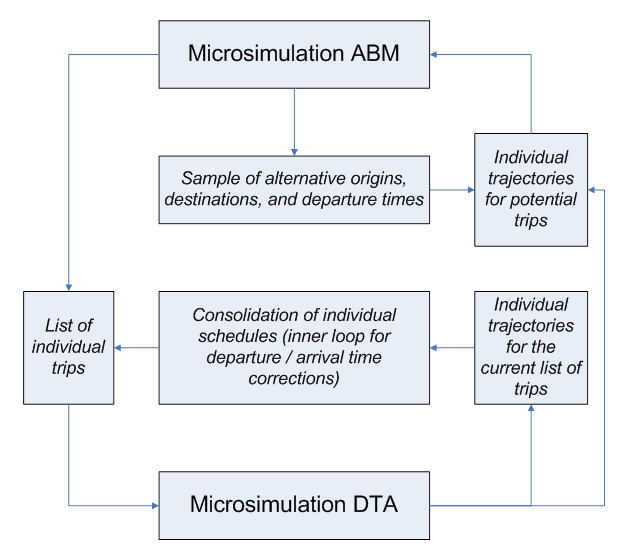

New methods of equilibration for ABM and DTA are presented in the figure below, where two innovative technical solutions are applied in parallel. The first solution is based on the fact that a direct integration at the disaggregate level is possible along the temporal dimension if the other dimensions (number of trips, order of trips, and trip destinations) are fixed for each individual. Then, full advantage can be taken of the individual schedule constraints and corresponding effects. The inner loop of temporal equilibrium includes schedule adjustments in individual daily activity patterns as a result of congested travel times being different from the planned travel times. The integration helps the DTA to reach convergence (internal loop), and is nested within the global system loop (where the entire ABM is rerun and demand is regenerated to approach an equilibrium between demand and supply). The second solution is based on the fact that trip origins, destinations, and departure times can be pre-sampled and the DTA process would only be required to produce trajectories for a subset of origins, destinations, and departure times. In this case, the schedule consolidation is implemented by corrections of the departure and arrival times (based on the individually simulated travel times) and is employed as an inner loop. The outer loop includes a full regeneration of daily activity patterns and schedules but with a sub-sample of locations for which trajectories are available. This integration also can be interpreted as a learning and adaptation process with limited information).

# Practical Convergence Methods

# Averaging

These methods have been borrowed from conventional trip-based modeling techniques, but can be used with microsimulation as well, as long as they are applied to continuous outputs/inputs like LOS variables and/or synthetic trip tables generated by the Moving Successive Averaging (MSA). Averaging can be applied to different components of the travel model, including trip tables, Level-of-Service variables, link traffic volumes, etc. (Vovsha et al. 2008).

# Enforcement

These methods are specific to microsimulation and designed to ensure convergence of “crisp” individual choices by suppressing or avoiding Monte-Carlo variability. These methods are currently at an early stage of theoretical development, with some empirical strategies showing very good results (Vovsha et al. 2008). Enforcement methods include (1) re-using the same random numbers or starting random seeds for certain choices that would ensure that the choice will be replicated if no change occurs to the inputs, (2) gradual freezing of portions of households or travel dimensions from iteration to iteration and (3) analytical discretizing of probability matrices instead of Monte-Carlo simulation.